The relationship between the music of the English rock band Queen and the other visual media is quite complex and can be analysed following different paths.

The iconography of the group spans several media and forms of communication, with the aim to increase the dramatic impact of the performance or the significant influence of the image of the band itself. From singles and LP covers to musical videoclips and even to the costumes used in live concerts, Queen always followed a precise form of visual communication deeply connected with their music: images in that sense amplify the power of music alone, giving the public a full entertainment.

A concert is not a live rendition of our album. It’s a theatrical event

Freddie Mercury

The invention in the last century of a totally new media – the cinema – gave new impetus not only to figurative arts, but even to music since these representations needed a cooperation between different forms of entertainment: a fluid and dynamic circulation of signs, sounds and images was therefore born to achieve this new aesthetic aim.

Regarding Queen and the music written specifically for movies, the relationship is in some manner different and even more dynamic, since the band has to cooperate with directors to obtain a balanced final product, that is still nowadays enjoyable and following a precise aesthetics: different artists (from musicians to film poster artists) cooperate to get a coherent product where several forms of arts merge together and create the perfect illusion of the story narrated in the movie.

Several arguments can be traced in this article:

- Relationship with movies: the soundtracks for Flash Gordon and Highlander

- Relationship with videogames: the soundtrack of The eYe

- Relationship with the musical: the development of the show We Will Rock You

Flash Gordon (1980)

Flash Gordon is the protagonist of a space opera adventure comic strip created and originally drawn by Alex Raymond: first published January 7, 1934, the strip was inspired by, and created to compete with, the already established Buck Rogers adventure strip. The comic strip follows the adventures of the main character Flash Gordon, a handsome polo player and Yale University graduate, and his companions Dale Arden and Dr. Hans Zarkov.

The story begins with Earth threatened by a collision with the planet Mongo. Dr. Zarkov invents a rocket ship to fly into space in an attempt to stop the disaster. Half mad, he kidnaps Flash and Dale. Landing on the planet, and halting the collision, they come into conflict with Ming the Merciless, Mongo’s evil ruler. The story then develops with the introduction of several characters and with the representation of alien worlds in which the leading hero is able to move and takes action.

Raymond began to draw Flash in the Sunday paper in his typical hyperrealistic way, full of dynamism, with an eye for details. His first drawings consisted of thick, greasy lines, long strokes, blackened and curved planes. Later on, he changed his style toward superb preciseness, which bestowed the glory of one of the greatest comic strip artists in history upon him.

Zvonimir Tošić – http://comics.cro.net/e-flash.html

He paid exceptional attention to the human form, which always dominated the frame, leaving an impression of extraordinary vitality, glorifying the beauty and grace of movements of the body, of intercourse between a man and a woman. Raymond was an incurable romantic and aesthete. He was also fond of experimenting. He developed and introduced the “feathering” technique (defining or softening a contour with a series of fine lines). He introduced square text baloons as well, followed by no-baloon dialogues…

Flash Gordon is now regarded as one of the best illustrated and most influential of American adventure comic strip: the original concept has then been translated into a wide variety of media, including motion pictures, television, and animated series and this demonstrates the longevity of the original project during the years and in several media with different forms of publications and final users.

He was also an influence on early superhero comics characters (it inspired the costumed iconography of Superman and the Batman), and his presence is now part of the culture and society amongst other well known heroes. Its influence on science fiction has been felt ever since, and it is alternatively mentioned as a countermodel for serious efforts within the genre, as a source of inspiration for later popular entertainment, notably for George Lucas’ Star Wars.

Most of the Flash Gordon film and television adaptations retell the early adventures on the planet Mongo with minor differences to better meet the other final media in which the story takes place. Often in these new versions the original spirit shifts, and in some manner the charachers are simplified and even their background is different, but the adjustments still keep the raw information and the peculiar details.

One of the most famous and popular version in which the hero is found is the 1980 movie, where the production emphasized Flash dazzling blondness, but associated it with sexual ambivalence rather than manichean heroism, and this is one detail that differs from the original conception of the strip. The parallel between the original comics trips and the later adaptions indicate that a different experience takes place, and this happens not only for the different media involved:

The various technological updates (in 1980 but also in the 2007 TV series) suggest that Raymond’s art is evocative precisely because it falls short of realism. The role of technical limitations should therefore not be overstated, and recent digital blockbusters have demonstrated the difficulty of capturing comic book imagery, even when this imagery is not tied to an idiosyncratic style.

Nicolas Labarre – Two Flashes. Entertainment, Adaptation: Flash Gordon as comic strip and serial

The 1980 film version is directed by Mike Hodges, and stars Sam J. Jones, Melody Anderson, Ornella Muti, Max von Sydow and Topol, with Timothy Dalton, Mariangela Melato, Brian Blessed and Peter Wyngarde in supporting roles. The film follows star quarterback Flash Gordon (Jones) and his allies Dale Arden (Anderson) and Hans Zarkov (Topol) as they unite the warring factions of the planet Mongo against the oppression of Ming the Merciless (von Sydow), who is intent on destroying Earth.

So the basis of the story recalls the original strip – and it focuses especially on the story published in the first years – but with some necessary adjustments both for the new media involved (the movie instead of the strips) both for the historical background (in the movie the character Flash is a football player instead of a polo one).

Flash Gordon is a mid-air skirmish of corny old-fashioned retrofuturism and knowing postmodernism, even as its veneer of homespun innocence keeps being subverted by the corrupting powers of kink. Every spacecraft here is absurdly phallic (at one point, Flash literally penetrates Ming with one), Ming’s daughter Princess Aura is a sexualised seductress with a lover in every port, the elaborate costumes come with the tang of fetishism, and Ming’s metal-masked, Vader-like head of secret police Klytus (Peter Wyngarde) – an all-new character – wields whips and chains like a gimpy BDSM dungeon master.

Shot in glorious Technicolor, Flash Gordon presents space not as a dark vacuum, but as a psychedelic vista of chemical swirls and polychromatic clouds. Hodges’ comic book caper is all cheeky, cheesy fun, with moustache-twirling bad guys, strong-jawed heroes, and every line dripping in self-conscious absurdity (not to mention innuendo).

ANTON BITEL – https://lwlies.com/articles/flash-gordon-joyous-comic-book-adaptation/

In the 1970s, several noted directors attempted to make a film of the story from the original comic strips. Federico Fellini optioned the Flash Gordon rights from Italian-American film proucer Dino De Laurentiis, but never made the film. George Lucas also attempted to make a Flash Gordon film in the 1970s. However, Lucas was unable to acquire the rights from De Laurentiis, so he decided to create Star Wars instead.

De Laurentiis also discussed hiring Sergio Leone to helm the Flash Gordon film; but Leone declined because he believed the script was not enough faithful to the original Raymond comic strips. Finally, the Italian producer hired Mike Hodges to direct the Flash Gordon film in the UK at Shepperton Studios after the departure of original director Nic Roeg.

Flash Gordon is like a fairy tale set in a discothèque in the clouds… There are no hidden themes in this comedy fantasy; everything is on the luscious surface.

Pauline Kael, The New Yorker, May 1, 1981

Queen met Flash Gordon in 1980 when they were asked to write the soundtrack for this new film adaptation: the rock band wrote the music mixing together the sounds of synthesizers and a real orchestra, giving thus the movie and the score a similarity with a classical opera for the general conception and the proportions (and this unusual use of electronic instruments that mime an orchestra anticipate the Freddie Mercury’s “BARCELONA” solo album from 1987).

Besides that, the use in the musical score of the leitmotiv recalls the Wagner’s revolutionary idea to connect the music and the character in order to underline some specific dramatic situations during the plot (and another reference to the German composer is the adoption in the movie, for a particular scene, of the bridal chorus from the opera Lohengrin but rearranged for electric guitar).

Following this way of musical composing, at least 3 main musical themes, connected to some of the movie main characters, can be found: Flash’s theme, Ming’s theme and Vultan’s theme. And to these we must add the Love theme and the Battle theme that will have a reprise too during the plot. This approach is not new in movies’ soundtracks, and one of the best examples of using repeated themes associated with characters or peculiar situations can be already found some years before in the Star Wars trilogy thanks to the music of John Williams.

In Flash Gordon the musical themes are always simple, but this detail helps to better recognize and memorize them by the viewer and to relate them with movies’ characters. For example, the Ming’s Theme written by Mercury is short and plain even with the use of some chromatic notes (and this underlines the personality of the villain of the story):

In Football Fight, the use of an ascending scale at the end of the musical phrase is opposed to the previous example, where a descending chromatic scale is linked to Ming’s character:

One of the best musical piece of the entire Flash Gordon soundtrack is undoubtedly the short fragment (less than 2 minutes in total) called The Kiss. Written by Freddie Mercury, it is characterized by high notes similar to a something ethereal and this short fragment anticipate the solo Freddie Mercury track Exercises In Free Love.

No clear words are sung, only short segments that seem a breath, similar to what happens on the screen where the main character Flash comes back to life after receiving the kiss cited in the title by the princess Aura:

Queen’s Flash Gordon soundtrack has been viewed as a surprising anomaly within the band’s discography by fans and critics alike, […] and the choice to release a soundtrack album seems like an odd one. The band was coming off “THE GAME”, a quadruple platinum smash. […] A Mad Peck comic strip for the rock magazine Creem summed up the commercial and artistic dilemma. The comic depicts Abbott and Costello (for no apparent reason) discussing the album.

Phil Sutcliffe – Queen. The ultimate illustrated history of the crown kings of rock

The use of electronic instruments (something unusual for Queen that started using them in the previous album “THE GAME” always from 1980) gives the movie a clear musical direction, so in this case the music shapes the final perception of the movie itself. In fact, even in the Star Wars movie trilogy some special effects were obtained with the use of synths, and therefore this kind of instrument has been connected with sci-fi movies since then.

The first example of an electronic instrument used in this context is the theremin in the Robert Wise movie The day the Earth stood still (1951) by composer Bernard Herrmann; in Forbidden planet (1956) directed by Fred M. Wilcox the soundtrack, written by Bebe and Louis Barron, consisted entirely of electronic sounds: the use of the instrument begat our fascination with representing the otherworldly (i.e. aliens, UFOs, and other extraterrestrial concepts) with markedly otherworldly sounds.

Queen’s music is in this project mainly instrumental, and a classical orchestral arrangement (by composer Howard Blake) can be heard all over the movie: but the orchestral section is always in background, and other electronic instruments emerge in the final score and remain in the listener’s memory. When Blake was commissioned to write the orchestral music section for Flash Gordon, he was given only 10 days to produce the results and the whole soundtrack – including Queen songs – was nominated for a BAFTA Award. It was, however, a disappointment to him that the makers of Flash Gordon did not use much of his score preferring the Queen songs in the final edit of the movie. Even today, the original full orchestral score has never been published.

Only two complete Queen songs with lyrics, Flash and The Hero, are part of this original soundtrack and can be heard during opening and credit titles, so they create a sort of a frame at the beginning and at the end of the movie (note that Raymond’s drawings feature heavily in the opening credits, as does the signature theme-song Flash). All Queen members wrote at least one track for this project and so all members were involved and gave their decisive contribution, as it will happen for the Highlander soundtrack as well.

The presence of music increases during the movie following the dramatic path of the story itself: in this case music empathizes what can be seen on the screen creating an aesthetic that merges sounds and images.

The artwork for the original LP cover has been conceived by Cream studio (the collaboration with Queen will go on for the Greatest Hits cover as well) and it features a very simple and essential design with a focus on the movie main character name/logo and a yellow background. Even the band name appears in small format, giving the priority to the movie instead than to music.

The overall project seems similar to a comic strip book cover and this idea is supported by the fact that the back cover features an image from the movie with Flash in evidence. In this case it’s not a random image that has been choosen, but the very last frame that closes the movie. So the whole LP album cover with its front and back pictures becomes and recalls in some manner a strip comic book: the artwork has an internal coherence with the music that finds its own place between these graphical frames.

The tracklist for the entire soundtrack is the following:

Flash’s Theme [Brian May]

In the Space Capsule (The Love Theme) [Roger Taylor]

Ming’s Theme (In the Court of Ming the Merciless) [Freddie Mercury]

The Ring (Hypnotic Seduction of Dale) [Freddie Mercury]

Football Fight [Freddie Mercury]

In the Death Cell (Love Theme Reprise) [Roger Taylor]

Execution of Flash [John Deacon]

The Kiss (Aura Resurrects Flash) [Freddie Mercury, Howard Blake]

Arboria (Planet of the Tree Men) [John Deacon]

Escape from the Swamp [Roger Taylor]

Flash to the Rescue [Brian May]

Vultan’s Theme (Attack of the Hawk Men) [Freddie Mercury]

Battle Theme [Brian May]

The Wedding March [arr. Brian May]

Marriage of Dale and Ming (…And Flash Approaching) [Brian May, Roger Taylor]

Crash Dive on Mingo City [Brian May]

Flash’s Theme Reprise (Victory Celebrations) [Brian May]

The Hero [Brian May]

One of the main highlights of the movie was always the detailed and colourful costumes, designed by none other than the legendary Italian costume designer Danilo Donati, who had worked on several Italian films under famous directors such as Pier Paolo Pasolini and Federico Fellini. Whilst the original comics, as well as the 1930s serials, had provided ample inspiration for the characters costumes, Donati’s designs were far more ornate and detailed than any previous depiction, showcasing his own design flair very clearly.

The Flash OST (original soundtrack) is a bizarre and hypnotic work when considered in isolation, well worthy of stoner devotion reserved for the likes of “Piper At The Gates Of Dawn” or the cool, modern appreciation of Morricone. It bleeds atmosphere and poise, but is not adverse to hilarity, even becoming hysterical at some points. A fine blend that is never too self-conscious or over-complicated. But married to the images that Mike Hodges provides, the work becomes an accomplished, slick and instinctive whole. Beginning with the main musical themes and continuing through similarities to operatic convention, it is a cohesive whole.

Daniel Ross – https://thequietus.com

Produced by Queen guitarist Brian May and Mack (something unusual for Queen career, since previous albums had all the members as producers and not only a single one), the Flash Gordon soundtrack – the first experiment of Queen in that artistic direction (it was one of the earliest high-budget feature films to use a score primarily composed and performed by a rock band, another previous example is The Who’s “TOMMY” from 1975) – was published on December 8, 1980, the same day of the movie world premiere.

We’d been offered a few [soundtracks], but most of them were where the film is written around music, and that’s been done to death – it’s the cliché of ‘movie star appears in movie about movie star’ but this one [Flash Gordon] was different in that it was a proper film and ha a real story which wasn’t based around music, and we should be writing a film score in the way anyone else writes a film score – we were writing to a discipline for the first time ever.

Brian May

The film had little success in England but all around the world it was not supported by a proper marketing campaign and it was a flop; it received overall positive reviews by critics. But years later it became a cult classic with fans of science fiction and fantasy for its atmosphere, to whom the soundtrack is a perfect match.

I’m VERY proud of our music for the Battle Sequence… it’s all very fresh on my mind… it was totally thrown together in the old-fashioned way… playing TO PICTURE – and there was a moment when, left carrying the can… because Queen was actually busy making another album at the same time… I got on a roll with the Hawkmen and their rescue attack… I could still ‘sing’ you that whole sequence… to me it’s totally a song. I’ll add a couple of interesting (perhaps) facts. This was the first time that we, as a band, recorded with synthesisers (previously we always had the declaration on our album sleeves “No Synthesisers”). And I believe that this really is the first time that a proper score, to something other than a story about musicians, was ever applied to a film by a rock band. It’s very common now, but I remember having a conversation with the amazing producer of this film, Dino de Laurentiis, early in the relationship… wherein he said… “The score of my movie cannot be rock music… it has never been done” And I said… “but it COULD be done”.

Brian May – https://brianmay.com

The original Flash music videoclip (made to promote the song) was filmed at Anvil Studios, London, in November 1980 and was directed by Don Norman. It shows the band performing the song to a screen showing clips from the film, in an iconographic short circuit where music and images merge together. It’s remarkable to notice that Brian May is playing in this videoclip an Oberheim OBX synthesiser, the same electronic instrument used in the movie soundtrack both for music and special effects: the videoclip in this manner suggests a studio recording session similar to the actual ones.

To promote the movie, Freddie Mercury wore a Flash theme-based t-shirt during concerts of the period; in live shows only Flash, The Hero and The Battle Theme were played because they were tracks more suitable for a live set being theme just not only instrumental or with a very short structure. Short songs from the soundtrack could not easily been separated from images since they were originally conceived to be part of another artistic rendition, the movie and not a live performance.

The original Flash singles releases on 7″ vinyl use mainly in European editions a blue/lilac background instead of the yellow version of the LP. This kind of standard for several markets is something new and unusual for Queen discography in these years since usually all countries have different picture sleeves and artworks (making them more collectable), at least until 1984 when all the picture sleeves around the world become almost identical and standardized.

Other countries (such as USA and Japan) focused instead on the original yellow layout with the logo put in evidence, and with the band logo in a bigger print than the LP version:

The South African edition, issued in promo editions as an invite to the movie premiere in that country without a picture sleeve, used instead the Flash Gordon logo on the label:

Later editions of the song issued on CD singles featured the usual yellow background and a new red one too. Several remixes of the song Flash were produced in 2002 with German producers Vanguard, mainly for dance and club charts.

In 2020, for celebrating the 40th anniversary of the movie, Queen released a limited edition (in 1980 copies) of the soundtrack on LP format; the item was made in a yellow picture disc that recalls the original artwork:

To achieve the best possible artwork in promoting the movie no less than three tenured fantasy/movie poster artists were hired in the Flash Gordon project: the final purpose was to sell the picture across the world with the help of stunning paintings that could anticipiate in some manners the atmospheres of the adaptation. First among these was British illustrator Philip Castle, whose mesmerising pre-production piece of the Battle for The Ajax was made into a foil print teaser:

For the theatrical advance poster, artist Lawrence Noble produced a piece that would be utilized for other merchandise such as the cover for the Flash Gordon book (see below) before being adapted for the final US Poster by Richard Amstel.

The original Flash Gordon artwork (as evident from the official movie programme for the premiere on December 10, 1980, and some other promo material from private collections) consisted of a black background and a different render of the logo itself. It was changed at the very last minute to the vivid yellow background and the definitive thunderbolt.

The promo items for the movie itself use the more usual combinations of colours and movie elements mixed in a different way for each country, with the characters Flash and Ming almost always in relevant position.

The drawings for the European and Japanese releases are by the Italian artist Renato Casaro, one of the most important and innovative film poster artist (amongst his collaborations there are the directors Sergio Leone, Francis Ford Coppola, Franco Zeffirelli): his style tries to merge the original comic strip side of Flash Gordon with the real actors that starred in the movie; these are fantasy-art style pieces which would arguably become the the most iconic of the Flash campaign.

His aesthetics in the beginning of the 80’s is deeply influenced by the use of airbrush as a new technique to give life to the characters, as it will emerge even some years later for the Rambo trilogy. Vivid colors and a continue research for the smaller details help to create a parallel universe in which the story takes place. In this way and with a single look the viewer can have a direct look at the world depicted and that he will better expolore with the vision of the movie itself.

Not always Queen are quoted in these posters as composers of the soundtrack, and in any case the name of the group is always printed in small formats: in these years the marketing for the movie was not affected by the composer who wrote the score. In some countries the illustrations for the movie posters or other promo material (such as movie programs) have been produced by the artist Richard Amstel, with a style very similar to the original concept imagined by Renato Casaro.

The promo and adverts for soundtracks underlined instead the group name in a more evident way and with the usual colours’ combinations, and with the last version of the movie logo:

Several items were then produced during the years to promote and celebrate the movie: the last version of the logo survived as final element, as the red/yellow combination. Among them some pinball machine tables (produced in 1981) with distinctive head plate:

In 1983 a video game adaptation for the Atari 2600 console was developed by Sirius Software and published by 20th Century Fox Games. The artwork recalls the movie posters without adding new elements.

Highlander (1986)

Six years later the Flash Gordon score, Queen decided to write the music for another movie, and in this case too it was again a sci-fi one: Highlander. This time, they preferred focusing on more standard songs-form structure, but they were strongly influenced by the story itself and its characters and therefore the soundtrack keeps these elements and gives them new form: even in this case the collaboration with the movie director was a central point in the musical score development and this partnership will go on in musical videoclips too, that are strongly related to the movie general atmosphere and elements (see for example the video for the song Princes of the Universe).

Highlander is directed by Russell Mulcahy and based on a story by Gregory Widen. It stars Christopher Lambert, Roxanne Hart, Clancy Brown, and Sean Connery. The film chronicles the climax of an ages-old war between immortal warriors, depicted through interwoven past and present-day storylines. The main character Connor MacLeod is portrayed as a person who has suffered loss and fears new attachments but who still pursues the possibility of love, maintains a sense of humor about life, and adopts a daughter whom he tells to keep hope and remain optimistic: all these elements influence Queen music and the lyrics of the songs as well.

The British rock band Marillion turned down the chance to record the soundtrack because they were on a world tour, and David Bowie, Sting, and Duran Duran were considered to do the soundtrack for the film. At the end the production asked Queen to be part of the project together with the original orchestral score of Michael Kamen and the National Philharmonic Orchestra.

The collaboration of the English band together with the American composer, who in his career will work with other rock groups (PinK Floyd, Aerosmith, Metallica, The Cranberries…) is deep, and musical themes flow from songs’ structures to orchestral ones with a coherent direction that keeps the whole score as a unique element and perfectly merges images seen on screen.

Queen songs’ structure is in this project classic, unlike from what happened in the previous Flash Gordon and long songs (with lyrics, no more only instrumental) can be heard several times during the movie: the presence of the music is constant, and the lyrics help to better understand what’s going on and suggest the character’s emotions underling the turning points in the plot.

Having worked with director, Queen have been able to create specific songs that recall the atmosphere of the movie (A Kind Of Magic, Princes Of The Universe, Don’t Lose Your Head) and that can underline the characters’ feelings or specific dramatic moments on screen (Who Wants To Live Forever, One Year Of Love, Gimme The Prize).

As for the previous film, Brian May was the more involved in this kind of project (and arranged in cooperation with Michael Kamen the scores played by the National Philharmonic Orchestra), even if the other members wrote specific dedicated songs. As the director Russell Mulcahy recalls in an interview:

I was at a point in my career when I could call in a few favours. Queen had done a great score for Flash Gordon, so we gave them a 20-minute reel of different scenes and they went: “Wow!” We’d only expected them to do one song, but they wanted to write one each. Freddie Mercury did “Princes of the Universe”, Brian May did “Who Wants to Live Forever”, Roger Taylor did “It’s A Kind Of Magic”.

The songs of the original soundtrack have been released in the “A KIND OF MAGIC” (the title itself is taken from a sentence that can be heard in the film) album from 1986, even if some versions on the album are different from the movie extracts. The only Queen song used in the movie that was not taken from the “A KIND OF MAGIC” LP is Hammer To Fall, that comes directly from their previous studio album “THE WORKS” (1984).

The tracklist, that contains even songs not present in the movie (One Vision, Pain Is So Close To Pleasure and Friends Will Be Friends) is the following:

One Vision [Queen]

A Kind of Magic [Roger Taylor]

One Year of Love [John Deacon]

Pain Is So Close to Pleasure [Freddie Mercury, John Deacon]

Friends Will Be Friends [Freddie Mercury, John Deacon]

Who Wants to Live Forever [Brian May]

Gimme the Prize [Brian May]

Don’t Lose Your Head [Roger Taylor]

Princes of the Universe [Freddie Mercury]

Who Wants To Live Forever (inspired to Brian May from a short segment of the movie he had the opportunity to see in pre-production) is without any doubt the most important song of the entire soundtrack. Its musical presence and influence can be heard several times in the movie – both as song and orchestral variations – and it merges both musical worlds of the film itself in a logical audiovisual relationship.

Note that the movie version of the song, in which Freddie Mercury sings both verses, has never been published, since the album version contains a verse sung by Brian May.

The cooperation with Michael Kamen as an orchestral arranger is evident from the full score of the song too, where rock’s instruments (3 different electric guitars, 2 Yamaha DX7 keyboards programmed for “organ sound”) are played together a classical orchestral section (with strings, French horns, trumpets and trombones) and this complexity in some manner sums the different aspect of the soundtrack itself, where so many different elements find a perfect balance:

Queen’s songs take the preposterous, bloated concept and elevate it into ever-more-preposterous, ever-more-bloated grandeur. Connor watches his lover age in their craggy Highland home and buries her as Freddie Mercury operatically blasts the heather with the stentorian operatic anguish of “Who Wants to Live Forever” – bolstered by string arrangements from soundtrack collaborator Michael Kamen. The proggy, heavy “Princes of the Universe” gives even the text of the opening credits a surging drama. “Here we are, born to be kings/We’re the princes of the universe!” The chords continue into the opening scene, where Connor sits in contemporary Madison Square Garden, watching hairy, bear-chested, spandex-clad wrestlers wriggle their fingers and hips flirtatiously before they bash together in sweaty struggle.

Noah Berlatsky – https://www.syfy.com

The five Kamen cues – “The Highlander Theme”, “Rachel’s Surprise / Who Wants To Live Forever”, “The Quickening”, “Swordfight at 34th Street”, and “Under the Garden / The Prize” – show a composer who is clearly still honing his craft. Despite the performance of the National Philharmonic Orchestra, much of the Highlander score feels very raw, as though Kamen was trying too hard to impress his employers with a vast array of flourishes, changes of tempo and style, and densely orchestrated action sequences. This is something that Kamen was guilty of quite a bit during the early years of his career […] and some may find his writing here lacks the smoothness and clarity of some of his later works. Despite this, there is still a great deal in Highlander to recommend. Kamen’s main Highlander theme is memorable – a two-note fanfare, echoed by a six note response in the horns – and it plays throughout much of the score. It’s a quintessential Kamen motif, with chord progressions and rhythmic ideas that those who have followed his career will recognize, and it gives MacLeod a noble, heroic identity. Kamen allows the theme to pass around his orchestra freely, from strings to brasses, and he augments his ensemble with electronics, a female solo vocalist, and even some region-specific instrumentalists, including bagpipes and a mandora, a type of medieval mandolin or lute.

Jonathan Broxton – https://moviemusicuk.us/2016/03/10/highlander-michael-kamen/

Highlander enjoyed little success on its initial theatrical release, grossing over $12 million worldwide against a production budget of $19 million, and received mixed reviews. Nevertheless, it became a cult film some years later and inspired film sequels and television spin-offs (where Princes Of The Universe is used for the title sequence in the television series). The tagline, “There can be only one”, has carried on into pop culture.

The original artwork for the LP cover was designed by Roger Chiasson, an animator who worked for several Disney movies. It depicts the four Queen members in a caricatural way, with some “magical details” that amplify the title of the album itself. These same elements will be used again for the A Kind Of Magic promotional videoclip, giving the whole project an internal coherence. The original sketches appear near-identical to the album’s cartoon figures of the band, with the style almost unchanged.

The iconographic relationship between Highlander and the band is even more complex, due to the fact that for many vinyl singles (both in 7 and 12 inch formats) the characters of the movie were chosen for the front covers instead of the band members.

This option in the Queen iconography is another step in the direction of merging the music and the images that is something peculiar for the English rock band, and it is a choice more natural and mature than what happened with the Flash Gordon releases. In several countries the artworks depicts the movie’s characters underlining that the songs are part of the soundtracks: these editions become in this way an ideal connection between the music and the movie.

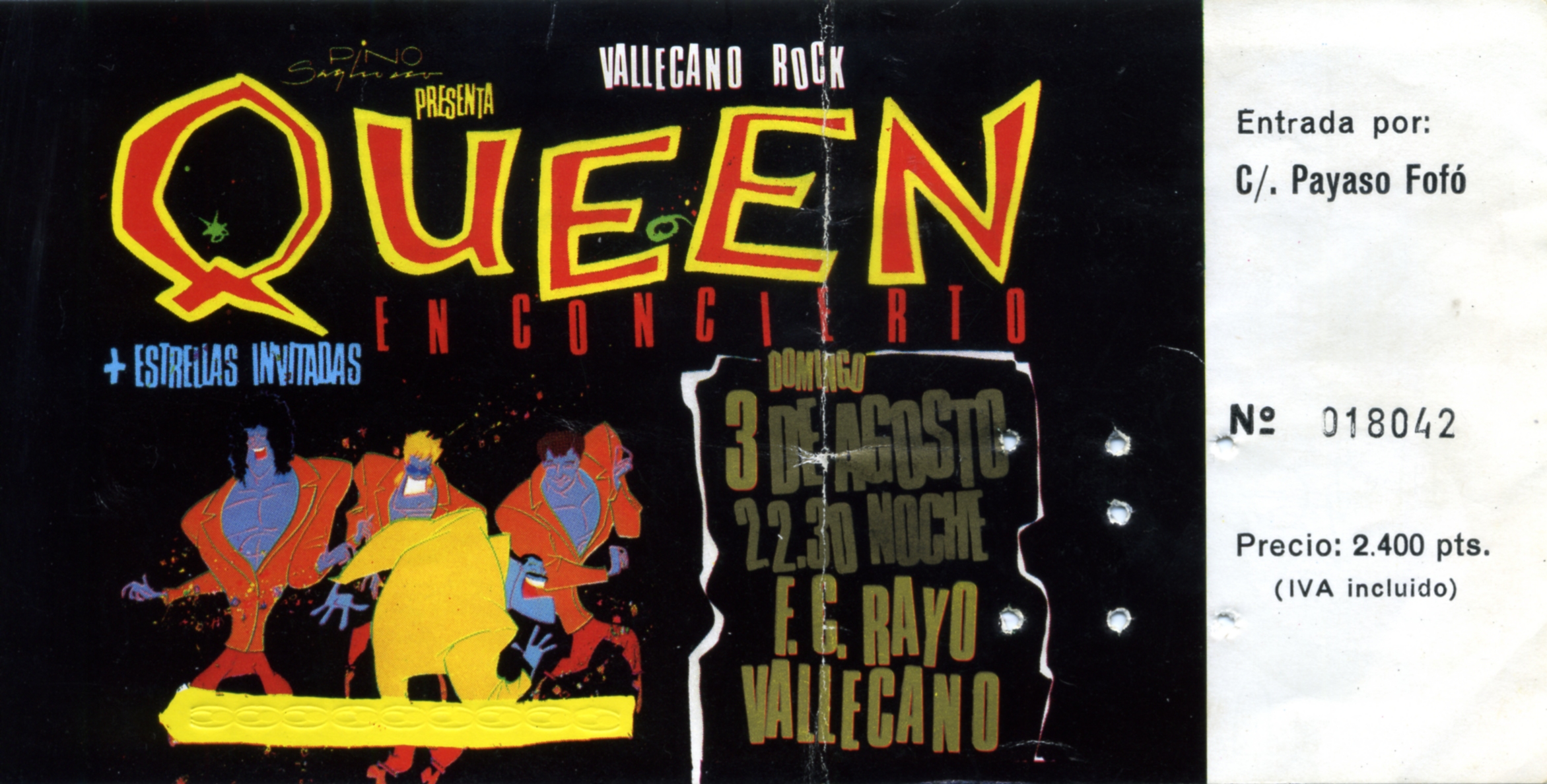

Even in some concert tickets of the time the “A KIND OF MAGIC” artwork (including an adapted print font) was used to better underline the album Queen were promoting at the time:

The collaboration with the Highlander movie director Russell Mulcahy was so deep that he directed the music videoclip for Princes Of The Universe. This videoclip was shot on February, 14th 1986 at Elstree Studios, London, on the Silvercup rooftop stage used for the film. It consists mostly of Queen performing the song, intercut with scenes from Highlander. Christopher Lambert reprises his role as Connor MacLeod for a brief appearance in the video, where he swordfights Freddie Mercury, who uses his microphone stand as a sword. Brian May is seen playing a Washburn RR11V instead of his usual Red Special.

Again, the connection between movie, music and images is merged in an intense exchange of mutual ideas that can be fit in any media of the franchise, and this helps to create an organic and coherent universe where the single element can be moved and still retain its influence and relations.

The British artist designer Brian Bysouth is the responsible for the concept of the movie poster and the general atmosphere for the graphic side. In an interview he recalls:

It was an enjoyable job and, fortunately, when asked to do a design for that type of film I was usually quick to identify what the key image should be. Phil Howard-Jones, the advertising director at EMI, who I did the work for, liked it very much and eventually he kindly returned it to me.

The final movie posters recall the main character with his sword, and the Queen name is underlined as authors of the soundtrack.

In contrast to what it happened with the several versions of the poster for Flash Gordon, in this movie the artwork is almost identical in each country (except in US, where a black and white close-up of Christopher Lambert was used). What it remains similar is the use of a dedicated logo for the title and the type of drawings similar to a comic book, even if the characters are easily recognizable with the actors.

Flash Gordon and Highlander: the Comparison

The following table shows side by side the main differences of the two movies, underlining the different approach of the band and the similarities in the creative process too, underling that for both movies each Queen member wrote at least one dedicated song.

| Flash Gordon (1980) | Highlander (1986) |

| Music is mainly instrumental | Music is made by sung tracks |

| An open orchestral structure can be heard all the time | Song structure is classic |

| Short musical segments repeated as Wagner’s leimotif when the main character (Flash Gordon) takes actions | Long complete songs |

| Only 2 complete songs at the beginning (opening titles) and at the end (credits titles) of the movie | Complete songs along all the movie |

| Additional orchestral arrangements by Howard Blake | Additional orchestral arrangements by Michael Kamen (in collaboration with Brian May) |

| The presence of music increases during the movie following the dramatic path of the story itself: in this case music gives emphasis to what can be seen on the screen | The presence of the music is constant during the movie and the lyrics help to better understand what’s going on |

| Music created by synths is used often as special effect and underlines the movie’s fiction atmosphere | Music is never used as a special effect |

| Wagner’s bridal chorus from opera Lohengrin is played by Brian May on guitar | A cover of New York, New York by Liza Minnelli is sung by Freddie Mercury |

Other Projects

Queen and his solo members collaborated during their career in many other soundtracks for movies or musicals, but never in a deep way such as for the Flash Gordon and Highlander projects, since they were not involved or collaborated with directors from the beginning of the movie itself.

In these examples, they wrote music (mainly one track per movie) and the soundtracks were often a collaboration with other artists, or their tracks were used for a movie, even if the music wasn’t originally conceived for that particular project.

This kind of soundtracks is the most frequent collaboration used nowadays in movies, where a classical orchestral composition is combined with music from other artists, mainly from rock and pop culture.

Some of the other projects were the following:

- Metropolis (1984 – Restored version of the classic 1927 movie). Freddie Mercury wrote the song Love Kills

- Zabou (1986). Freddie Mercury wrote the song Hold On for the movie

- Biggles (1986). John Deacon wrote the song No Turning Back

- Time (1986). Freddie Mercury wrote the song Time for the Dave Clark’s musical

- Night And The City (1992). The soundtrack contains the Freddie Mercury’s cover of the classic song The Great Pretender

- Rise Of The Robots (1994). Although the game boasted May’s soundtrack, only The Dark appeared in the final release. May did in fact record a full soundtrack to the game, but it was postponed by his record company, causing Mirage to proceed without May’s musical contribution, with the exception of short guitar sounds

- The Amazing Spider Man (1995). Brian May wrote the main theme of the audio drama broadcasted by BBC

- Small Soldiers (1998). A remix of the song Another One Bites The Dust was recorded with the rapper Wyclef Jean

- Furia (1999). Brian May wrote the soundtrack for this movie directed by Alexandre Aja

- A Knight’s Tale (2001). Queen collaborated with the songs We Will Rock You and We Are The Champions (newly recorded with Robbie Williams)

The eYe

In 1998 the English group decided to give their music a new life bringing it to a videogame, for the project called The eYe: this time the original Queen songs were newly mixed in order to achieve a better integration with the action-adventure electronic videogame structure, focusing mainly on music and disregarding the lyrics.

We have in this way new versions of well-known songs that focus mainly on music and without the voices several instrumental details can be heard for the very first time: songs are heard in a new way leaving the listener the focus on the game instead of on lyrics. This doesn’t mean music is merely a background because the integrations with the game and with Queen iconography is deep and give the whole project a new level.

Even the structure of the songs themselves changed to better meet the needs of the new media (several songs can be heard in a loop circle): this can be read as new possibility of the music that shapes itself accordingly to the final visual media in which it will be used, in a challenging transformation that is deeply connected with a new aesthetic never seen before.

The eYe was released by Electronic Arts on 5 discs (called “The Arena Domain”, “The Works Domain”, “The Theatre Domain”, “The Innuendo Domain” and “The Final Domain”), and featured music remixed by the producer Joshua J. Macrae at Roger Taylor’s studio in Surrey.

The game is set in the future where the world is ruled by an all-seeing machine called “The eYe” which has eradicated everything that promotes creative expression. The player takes the role of Dubroc, a secret agent of The eYe who in the course of his duties has re-discovered a database of popular rock music, and is sentenced to death in “The Arena”, a live television show broadcast through satellites to the world in which the contestant battles fighting arena champions called the Watchers. From there Dubroc goes on a quest to destroy The eYe, a sort of Orwell’s “Big Brother”.

Many elements of the story were later adapted into the Queen musical We Will Rock You: so we can see another clear example of how their music could be shaped for different artistic products, from movies to videogames and musical too.

The soundtrack for the game The eYe has never been officially published. Divided in 5 discs, the tracklist is the following:

Disc 1 – The Arena Domain

Arboria

Made in Heaven (loop)

I Want It All (instrumental, remix)

Dragon Attack (instrumental, remix)

Fight From The Inside (instrumental)

Hang On In There (intro)

In The Lap of the Gods… Revisited (edit, vocals)

Modern Times Rock’n’Roll (instrumental)

More Of That Jazz (instrumental)

We Will Rock You (commentary mix)

Liar (intro)

The Night Comes Down (intro)

Party (instrumental)

Chinese Torture (usual version)

I Want It All (instrumental, remix)

Disc 2 – The Works Domain

Mustapha (intro, vocals)

Mother Love (instrumental)

You Take My Breath Away (instrumental)

One Vision (intro)

Sweet Lady (edit, vocals)

Was It All Worth It (instrumental, edit)

Get Down, Make Love (instrumental, remix)

Heaven For Everyone (instrumental)

Hammer To Fall (instrumental)

Tie Your Mother Down (intro)

One Vision (instrumental, remix)

It’s Late (edit, vocals)

Procession (usual version)

Made in Heaven (instrumental, remix)

Disc 3 – The Theatre Domain

It’s A Beautiful Day (remix)

Don’t Lose Your Head (instrumental)

Princes Of The Universe (instrumental, remix)

A Kind Of Magic (instrumental)

Gimme The Prize (remix, vocals)

Bring Back That Leroy Brown (edit, vocals)

Ha Ha Ha, It’s Magic! (vocal sample)

You Don’t Fool Me (instrumental)

Let Me Entertain You (instrumental, intro)

Khashoggi’s Ship (instrumental)

Forever (usual version)

Don’t Try So Hard (edit, vocals)

Was It All Worth It (intro)

Disc 4 – The Innuendo Domain

Brighton Rock (intro)

I’m Going Slightly Mad (instrumental)

Bijou (instrumental, edit)

Khashoggi’s Ship (instrumental)

The Show Must Go On (instrumental, remix)

The Hitman (instrumental, edit)

Too Much Love Will Kill You (edit, vocals)

I Can’t Live With You (instrumental, remix)

Love Of My Life (harp intro only)

Disc 5 – The Final Domain

Death On Two Legs (intro)

Death On Two Legs (instrumental)

Ride The Wild Wind (instrumental, remix)

Headlong (instrumental)

Breakthru (instrumental)

Hammer To Fall (instrumental)

Gimme The Prize (instrumental, remix)

The Hitman (instrumental, remix)

Don’t Lose Your Head (usual version)

Gimme The Prize (vocals, remix)

Although the game graphics may be nowadays outdated, they were conceived to give an idea of what a Queen-related universe could be. Following this idea, many elements of the virtual world depicted in the game recall graphical elements originally found in Queen album covers, or characters found in Queen lyrics. For example, the Le Roy Brown poster visible in some scenes recalls directly the Bring Back That Leroy Brown song:

The “INNUENDO” artworks (inspired by the French caricaturist Grandville) is visible at the end of the game. So an original image conceived originally for a magazine will become an LP cover and later an animated detail for a videogame.

We Will Rock You: The Musical

We Will Rock You is a jukebox musical based on the songs of British rock band Queen with a book by Ben Elton. The musical tells the story of a group of Bohemians who struggle to restore the free exchange of thought and fashion, and live music in a distant future where everyone dresses, thinks and acts the same. Musical instruments and composers are forbidden, and rock music is all but unknown.

Directed by Christopher Renshaw and choreographed by Arlene Phillips, the original West End production opened at the Dominion Theatre on 14 May 2002, with Tony Vincent, Hannah Jane Fox, Sharon D. Clarke and Kerry Ellis in principal roles. Although the musical was at first panned by critics, it has become an audience favourite, becoming the longest-running musical at the Dominion Theatre, celebrating its tenth anniversary on 14 May 2012.

The eleventh longest-running musical in West End history, the London production closed on 31 May 2014 after a final performance in which Brian May and Roger Taylor both performed. A number of international productions have since followed the original, and We Will Rock You has been seen in six of the world’s continents. Many productions are still active globally.

According to Brian May, Queen’s manager Jim Beach had spoken with the band about creating a jukebox musical with Queen’s songs since the mid-1990s. Initially, the intent was to create a biographical story of Freddie Mercury. About this time, Robert De Niro’s production company Tribeca Productions expressed interest in a Queen musical, but it found the original idea difficult to work with.

In 2000, Ben Elton was approached to start talks with May and Taylor on the project. He suggested taking the musical down a different path than initially imagined, creating an original story that would capture the spirit of much of their music. He worked closely with May and Taylor to incorporate Queen’s songs into the story. Elton has also stated that he was in part inspired by the computer-controlled dystopia of the 1999 science-fiction film The Matrix. The script was eventually completed midway through 2001.

Queen music is shaped in a new form again for this kind of media and show and the story itself, with some elements taken from the game The eYe, is deeply connected to the characters originally present in the songs’ lyrics: Galileo (from Bohemian Rhapsody), Killer Queen (from the song Killer Queen), the Gaga kids (Radio Gaga), Khashoggi (Khashoggi’s ship) and so on. Again, the music reinvents and reimagines itself breaking the rules of musical genres and breathing a new life.

Conclusions

Regarding the details of soundtracks, Queen wrote for the mentioned two sci-fi movies following a particular principle: if usually when movie directors or producers choose a rock group or artist to write a soundtrack, it is mainly a single track that can be heard at the end credits. But for Queen the process is more articulated and deeper: they wrote many songs that were used during all the movies, and their music is merged with the more classic orchestral scores composed by Howard Blake (for Flash Gordon) and Michael Kamen (for Highlander).

Therefore, the relationship with movies is far more complex and vivid than in other examples we may find in recent soundtracks. Queen had the possibility to follow the script and the shootings and, in that way, they could create a music that better merge with images, since it was created together and not simply just added later: this idea gives the whole project an internal structure and coherence that still keep it valid after several years.

More in general, one can notes that throughout their long career, Queen has peculiarly worked with many visual artists, being able to harmonize their music with a large variety of media (soundtracks, musicals, videogames), and this characteristic has contributed to enrich their iconic impact largely beyond the music world.

The impact of their iconography can therefore be traced in vinyl releases and in several other parallel projects, and this shows that a precise idea was conceived to expand the possibility of the simple music to other visual arts in a mutual exchange full of tiny details and hidden references. The media involved in this process could be a movie, a videogame or a musical, but in all these examples the deep link with the music is evident and isn’t strictly limited to the field of the final product: the technical challenges are override as well, even when (as for the videogame The eYe) some aspects are nowadays outdated. All these relationships create an artistic aesthetic deeply connected both with music both with visual arts, with an idea that goes beyond the material support and finally becomes art.

© Nicola Bizzo

Links useful for this article:

- https://costumedesignarchive.blogspot.com/2020/12/flash-gordon-1980.html

- https://www.gordonisalive.com

- http://comics.cro.net/e-flash.html

- https://lwlies.com/articles/flash-gordon-joyous-comic-book-adaptation/

- https://flypaper.soundfly.com/discovery/sounds-future-history-primer-synths-sci-fi-movies/

- https://journals.openedition.org/comicalites/249?lang=en#ftn17

- https://www.syfy.com/syfy-wire/highlander-rules-because-of-queens-rip-roaring-soundtrack

- https://www.filmonpaper.com/posters/highlander-quad-uk

- https://moviemusicuk.us/2016/03/10/highlander-michael-kamen/

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment.